“Teachers are not performers in the traditional sense of the word in that our work is not meant to be a spectacle. Yet it is meant to serve as a catalyst that calls everyone to become more and more engaged…”

–hooks, 1994, p.11

I understand higher education as serving two main purposes: 1) to support the flourishing of individual humans in their entirety; and 2) to promote the thoughtful examination of one’s perspectives and experiences in conjunction with those of others to work towards just and equitable outcomes. Engagement with the field of literacy studies has empowered me to cross disciplinary boundaries–my roles in professional organizations and my scholarship speak to this deep integration. Conversing and working closely with others within and across academic “silos”–reading education, early education for citizenship, and culturally responsive and sustaining pedagogies, among others-has greatly benefited my scholarship and, in turn, my teaching. I am better positioned to appreciate and support the strengths and needs of a wide range of people because of my deeply meaningful professional collaborations. These relationships in conjunction with my relationships with students have enabled us to co-design instructional spaces and experiences that serve the two purposes of higher education just identified.

In all courses I prioritize the co-construction of learning experiences with all community members (Freire, 2000). Together we decide what a welcoming and equitable learning environment means for us in this specific moment and context. We do this by examining who we are individually and collectively and as well as our previous relationships with content and pedagogy. For example, we typically discuss how to go about ensuring everyone’s voice is appreciated at the start of the semester. We reflect on our past experiences participating in classes and on the value we associate with our own and our community members’ voices. Though we typically come to the conclusions that our voices are all highly valuable and that some are projected more vocally and more often than others, students generally hold a range of communicative preferences and ideas about how to work towards more equitable participation and engagement in class.

This past year a group of students requested that they respond to regular, informal, low-stakes prompts when reading, viewing, or listening to new information instead of taking quizzes or writing lengthy papers. We utilized Peardeck to integrate these prompts into our learning, review our responses individually and together, and build off of the community’s foundation of knowledge and ideas. Additionally, the group expressed a preference for projects and performance tasks over other summative forms of assessment. Together we identified where we needed to grow and set individual and communal goals: multiple students struggled to distinguish between and apply lessons primarily targeting phonemic awareness concepts and those targeting phonics. Within a performance task, pairs of students sorted lessons into each category and after reviewing them carefully, designed their own lessons with distinct reader profiles in mind.

The group decided that upon having a solid foundation in early literacy concepts, models, theory, and research, they were ready to take turns leading the class in pairs or small groups. These student-led sessions began about eight weeks into the semester. At first the students facilitated discussion around and practice with a variety of early literacy assessments, lessons, and interventions. Together we identified strengths and weaknesses of materials and posed and explored questions related to them. In the final weeks of the semester, the students planned and presented integrated, culturally responsive, early literacy lessons; they practiced implementing their lessons with us and we offered feedback with which they made changes. During the final weeks of class, they invited us to learn more about early literacy topics of specific interest to them. A particularly memorable presentation involved evaluating wordless picture books for representation issues and stereotypes.

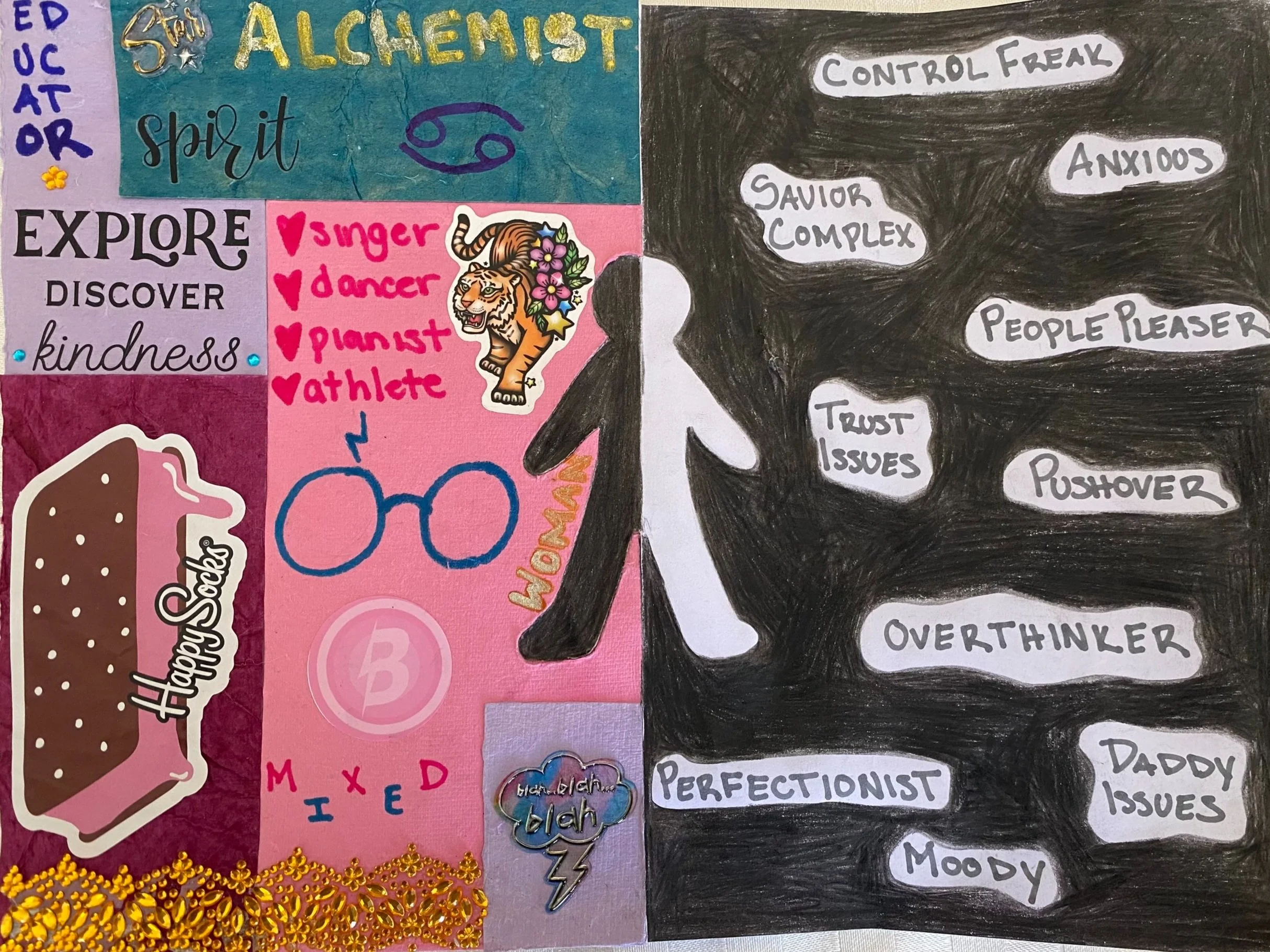

Like Brighouse (2012; 2005) and others, I understand flourishing as a whole human to require plentiful opportunities for exercising one’s autonomy in supported ways. Such opportunities should extend far beyond literacy content and pedagogy. To more holistically support students’ developing capacities for autonomy, and, in turn, their flourishing, I invite them to learn about themselves and their peers in individually meaningful ways. Art is one mode of communication and representation I have found to resonate with many. Together we often use art and visual literacy strategies to learn about our own and others’ multifaceted identities; not only are students often better able to mine their core values and beliefs this way, but they are also able to maximize their control (e.g., pace, tone) over the process–which, in my experience, can be intimidating for many. Relatedly, I strive to cultivate an appreciation for fellow community members’ interests and advancement outside of the classroom. Whether it is an LGBTQIA+ rally, a play, a concert, an art show, or a football game, I invite my students to share their extracurricular involvement–to the degree they are comfortable–and encourage our community to support one another through their presence and participation–as it makes sense for each individual–at extracurricular events .

Recently, a group of students and I attended an online presentation by peers to raise awareness about LGTBQIA+ flags that mattered to them. Another group of students and I attended a play to support a peer. I also encouraged the administration to print and hang a large mural in the School of Education suite depicting a piece of artwork sophomore education majors created to symbolize equity, inclusivity, and care. I sincerely believe that celebrating students’ identities by means of being present at extracurricular activities supports their flourishing and our (the observers’) flourishing in a multitude of ways including by bringing our attention to alternate legitimate ways of being in the world.

Finally, across all courses I invite dialogue on a range of issues relating to educational justice. Using our investigations of privilege and oppression specific to our individual multifaceted identities as an entry point, we consider how literacy education and education more broadly has historically reinforced patterns of domination and oppression. In ED 221 (Emergent Literacy) we focus specifically on cultural, social, and political contexts, key historical events (e.g., the war on poverty, English-only immersion legislation) and contemporary rifts (e.g., reading wars, accountability shove-down), as well as routines and practices students commonly identify as oppressive (e.g., reading groups, tracking, pull-out interventions). We also engage in regular audits of children’s literature for representation, stereotypes, and a variety of forms of bias (e.g., racial, sex, gender, dis/ability). By reflecting on our individual experiences with injustice we are able to more honestly begin to understand how injustice has impacted others. However, shallow engagement does not lend itself to praxis. Therefore, we study how others (e.g., Dr. Rudine Sims Bishop, Dr. Mariana Souto-Manning, Dr. Vivian Vasquez) have successfully and tirelessly worked with children and teachers to fight racial, cultural, linguistic and other forms of domination and oppression through literacy instruction. Students often come to the conclusion that children’s cultural identities must be affirmed in order for them to learn–and live–well. In closing, through our co-construction of environments, content, and pedagogies, we support each other in leaving our good marks on our shared educational spaces and also on the world.

hooks, b. (1994). Teaching to Transgress. Routledge.

Freire, Paulo, 1921-1997. ( 2000). Pedagogy of the Oppressed. Continuum,

Brighouse, H. (2012). Moral and political aims of education. In H. Siegel (Ed.), The Oxford Handbook of Philosophy of Education (1st ed., pp. 35-51). Oxford University Press.

Brighouse, H. (2005). On Education. Routledge.